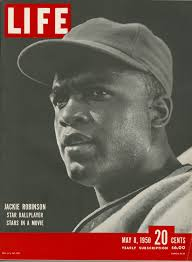

On May 10, 1950, baseball legend Jackie Robinson made history once again — this time off the field — by becoming the first African American to appear on the cover of Life magazine. In the publication’s 13-year history up to that point, no Black individual had ever graced its front page. Robinson’s appearance marked a significant cultural milestone, reflecting his role not only as a sports icon but also as a national figure of dignity and change. His presence on one of America’s most widely circulated magazines signaled a slow but meaningful shift in how Black excellence was represented in mainstream media.

On May 10, 1994, Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela was inaugurated as the first Black and democratically elected President of South Africa. Held at the Union Buildings in Pretoria, the ceremony marked the official end of apartheid and the beginning of a new era of multiracial democracy. More than 1,000 dignitaries from around the world, including U.S. Vice President Al Gore and Cuban leader Fidel Castro, were in attendance. Mandela’s inaugural speech emphasized unity, forgiveness, and the collective rebuilding of a “rainbow nation.” His election was the result of the first free and fair elections in the country’s history, with over 20 million people casting their votes. The moment symbolized not just political change, but global hope and the triumph of justice over oppression.

On May 10, 1963, Rev. Fred L. Shuttlesworth, a key leader in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), announced a partial victory in the Birmingham Campaign. An agreement was reached between civil rights leaders and white business leaders to begin desegregating public facilities and to release jailed demonstrators. This compromise marked a turning point in one of the most influential civil rights movements of the 1960s. Though limited in scope, the agreement helped end weeks of nonviolent protests that had drawn national attention to racial injustice and police brutality in the Deep South. Shuttlesworth’s fearless activism, alongside Martin Luther King Jr. and others, helped lay the groundwork for the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

On May 10, 1962, Southern School News reported that 246,988 Black students—just 7.6% of the Black public school population—were attending integrated schools across 17 Southern and Border States and the District of Columbia. This report, released eight years after the landmark Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision, highlighted the painfully slow pace of desegregation in American education. Despite federal mandates, widespread resistance from segregationist lawmakers and local communities continued to limit Black students’ access to equal educational opportunities. The publication’s data underscored the systemic barriers that persisted well into the 1960s and served as a sobering reminder that legal victories alone were not enough to dismantle institutional racism.

On May 10, 1951, civil rights attorney and educator Z. Alexander Looby was elected to the Nashville City Council, becoming one of the first Black council members in the city since Reconstruction. A fierce advocate for racial justice, Looby had already gained national attention for defending Black students in desegregation cases and for standing up to institutional racism in Tennessee. His election signaled a turning point in Southern politics and helped lay the groundwork for Nashville’s pivotal role in the Civil Rights Movement during the 1960s. Looby’s legacy lives on as a symbol of legal resistance, public service, and community empowerment.

On May 10, 1919, a violent race riot broke out in Charleston, South Carolina, when a confrontation between white U.S. Navy sailors and Black residents escalated into a night of chaos. The unrest resulted in the deaths of at least two Black men and injuries to dozens more. White mobs—many of them servicemen—looted Black businesses and attacked Black citizens with little intervention from local authorities. This event marked one of the early flashpoints of what would become known as the Red Summer of 1919, a period of widespread racial violence across the United States following World War I, driven by economic tensions, returning Black veterans demanding civil rights, and white backlash.

On May 10, 1837, Pinckney Benton Stewart (P.B.S.) Pinchback was born in Macon, Georgia. Born to a formerly enslaved woman and a wealthy white planter, Pinchback would go on to make American history during the Reconstruction Era. After the Civil War, he entered Louisiana politics and rose through the ranks as a fierce advocate for civil rights and education.

In 1872, Pinchback became lieutenant governor of Louisiana, and when the sitting governor was impeached, he stepped into the role. For 43 days, Pinchback served as acting governor, becoming the first African American to hold the office of governor in any U.S. state. He later helped establish Southern University and fought for the political representation of Black Americans during the volatile post-Civil War years.

On May 10, 1775, Black patriots stood alongside colonial militias in the first major offensive action of the American Revolutionary War—the capture of Fort Ticonderoga in New York. Led by Ethan Allen and the “Green Mountain Boys,” this surprise dawn attack secured a critical strategic point without bloodshed. Among the forces were free and enslaved Black men who risked their lives for a cause that would not yet recognize their full humanity. Their early participation in the war highlighted both the contradictions of liberty and the courage of those who demanded it from the start.

On May 10, 1652, John Johnson, a free Black man in colonial Virginia, was officially granted 550 acres of land in Northampton County. The land was awarded under the “headright” system, which offered land in exchange for transporting laborers—Johnson had imported eleven individuals. His acquisition of land during a time when Black freedom and property rights were rare in English colonies is a striking example of early Black agency in America’s colonial history. Johnson’s story reflects the complex realities of race, labor, and legal status in 17th-century Virginia—decades before slavery was fully codified in law.

© 2025 KnowThyHistory.com. Know Thy History